'Stamp out Paper Mills' - Science Sleuths on How to Fight Fake Research

Send us a link

In the latest twist of the publishing arms race, firms churning out fake papers have taken to bribing journal editors.

Predatory journals - even the term is controversial - have been a vexing problem for many years, and have certainly been a subject of coverage at Retraction Watch and elsewhere.

To thwart publishing rackets that undermine scholars and scholarly publishing, legitimate journals should show their workings.

One of the most fundamental issues in academia today is understanding the differences between legitimate and questionable publishing. This study's findings show that neither the impact factor of citing journals nor the size of cited journals is a good predictor of the number of citations to the questionable journals.

As part of a misconduct crackdown, Chinese funders are penalizing researchers who commission sham journal articles from 'paper mills', but some say the measures still don't go far enough.

Scopus has stopped adding content from most of the flagged titles, but the analysis highlights how poor-quality science is infiltrating literature.

Analysis of hundreds of articles in predatory titles shows that 60% have never been cited.

Predatory publishing has emerged as a professional problem for academics and their institutions, as well as a broader societal concern, bringing to the fore a debate over what constitutes legitimate science.

While the characteristics of scholars who publish in predatory journals are relatively well-understood, nothing is known about the scholars who review for these journals. This article aims to shed light on the reviewers for predatory journals.

Many of these titles have some editorial oversight - but the quality of reviews is in question.

By Rick Anderson, President of the Society for Scholarly Publishing.

Study suggests that 'predatory' spam targeted specifically at scholars costs universities $1.1 billion annually.

Predatory publishers' papers - long feared to contaminate the literature - may have little research impact.

Study finds that the number of publications in open access journals rises every year, while the number of publications in questionable journals decreases from 2012 onwards. Both early career and more senior researchers publish in questionable journals.

How many articles from predatory journals are being cited in the legitimate (especially medical) literature? Some disturbing findings.

Just how big a problem is predatory publishing? Simon Linacre reflects on the news this week that Cabells announced it has reached 12,000 journals on its Journal Blacklist and shares some insights into publishing’s dark side.

Given the reality of fraudulent publishers and their deceptive practices, will institutions consider more strongly guiding author choice of publishing venue in order to protect institutional reputation?

Publications in predatory journals have already infiltrated citation databases such as PubMed and Scopus. Researchers, academic institutions, journals, publishers and research funders will need additional strategies to prevent the further spread of predatory publications.

Science journalist attends a predatory conference and interviews scientists involved.

The National Library of Medicine has quality control procedures in place, but some researchers believe additional scrutiny is necessary.

Two years after its initial entry into the marketplace, Cabell's Blacklist has matured into a carefully crafted and highly useful directory of predatory and deceptive journals.

The Federal Trade Commission accused Omics International, a publisher in India, of operating hundreds of fake research journals with deceptive business practices.

Deceptive publishing (aka predatory publishing) has been a growing problem for years now. What do we know about it? How should we respond?

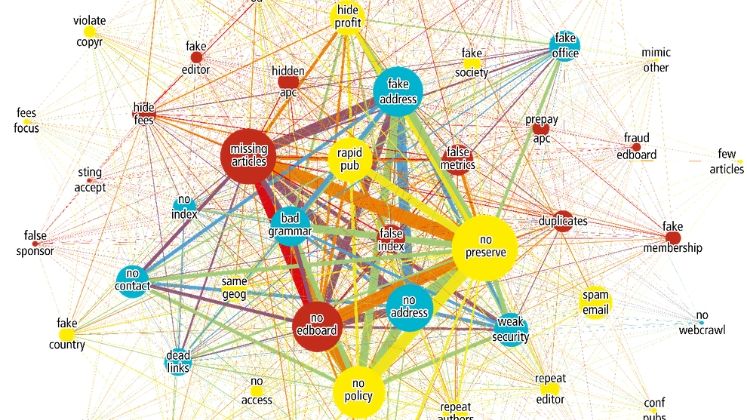

Despite growing awareness of predatory publishing and research on its market characteristics, the defining attributes of fraudulent journals remain controversial. The authors aimed to develop a better understanding of quality criteria for scholarly journals by analysing journals and publishers indexed in blacklists of predatory journals and whitelists of legitimate journals and the lists’ inclusion criteria.

If South Africa truly wants to encourage good research, it must stop paying academics by the paper.